Projected future water availability in Africa: A continent scale - Part one.

So far in this blog we've investigated some of the causes water insecurity and the changing geographical perspective from causes to consequences. This post will be based upon the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, chapter 22 (Niang et al. 2014), with data, figures and assessments derived from this in-depth report. Part one of this post showing the general continent scale projections, whilst part two and three is going to look at specific national and local scale case studies of future water projections.

As we have seen in the past blog posts that I've put up, there is significant literature and interactive publications that highlight the significant changes that environmental change is causing on the hydrological cycle. Examples such as 'Day Zero' in South Africa (Capetown gov, 2018) and substantial migration from Niger to Nigeria due to the decrease in water availability highlights clearly that the dire consequences that we were predicted have already manifested themselves; impacting a range of contexts, from agriculture and job availability to domestic usage. However, with any projections of future events, there is substantial room for uncertainty associated with the modelling; thus, the projections highlighted here today should not be taken as gospel. So let's jump into it then!

So what are the future projections? There is a range of different data sets and statistical models that have been produced by a range of organisations. However, I am going to focus on the projections by the IPCC in their forth assessment report and the key issues highlighted by the African Development Bank (ADB). The ADB state three main physical threats to water in Africa:

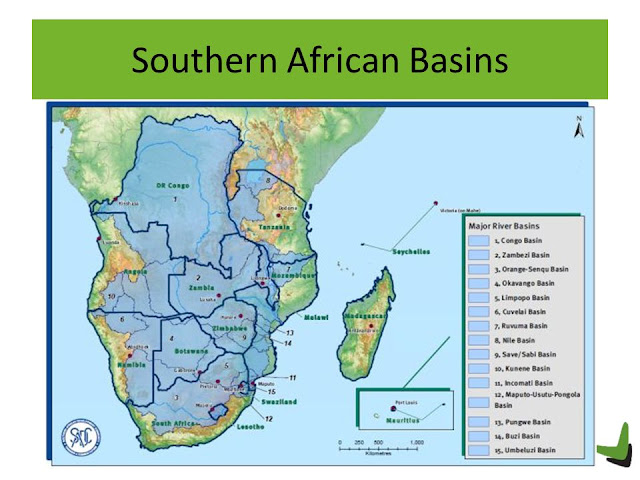

1. The increasing multiplicity of transboundary water;

2. Extreme spatial and temporal variability of climate and rainfall, coupled with climate change;

3. Growing water scarcity, shrinking of some bodies of water, and desertification.

This three threats to water security in Africa are only projected to be put under ever more pressure into the 21st century. Climate change is affecting the hydrological cycle and inputs/outputs from the system across Africa; however, it is important to remember that this change is not homogenous or linear. The projections found by the IPCC highlight this spatial and temporal variability. Figure 1.1 shows the annual temperature change across Africa with the value compared against the mean from 1986-2005. It highlights that they is three main bands of warming across the African continent. North Africa is projected to experience the spatially largest area and more intense warming, with annual mean temperature changes of up to 6 degrees by late 21st century. This intense projected temperature change is mirrored in Southern Africa; again with projections of up to 6 degrees of warming by late 21st century estimations. However, what is interesting is that central and Eastern Africa in projected to see annual temperature increases by late 21st century below that of the north or south from the RCP8.5 projections.

As we have seen in the past blog posts that I've put up, there is significant literature and interactive publications that highlight the significant changes that environmental change is causing on the hydrological cycle. Examples such as 'Day Zero' in South Africa (Capetown gov, 2018) and substantial migration from Niger to Nigeria due to the decrease in water availability highlights clearly that the dire consequences that we were predicted have already manifested themselves; impacting a range of contexts, from agriculture and job availability to domestic usage. However, with any projections of future events, there is substantial room for uncertainty associated with the modelling; thus, the projections highlighted here today should not be taken as gospel. So let's jump into it then!

So what are the future projections? There is a range of different data sets and statistical models that have been produced by a range of organisations. However, I am going to focus on the projections by the IPCC in their forth assessment report and the key issues highlighted by the African Development Bank (ADB). The ADB state three main physical threats to water in Africa:

1. The increasing multiplicity of transboundary water;

2. Extreme spatial and temporal variability of climate and rainfall, coupled with climate change;

3. Growing water scarcity, shrinking of some bodies of water, and desertification.

This three threats to water security in Africa are only projected to be put under ever more pressure into the 21st century. Climate change is affecting the hydrological cycle and inputs/outputs from the system across Africa; however, it is important to remember that this change is not homogenous or linear. The projections found by the IPCC highlight this spatial and temporal variability. Figure 1.1 shows the annual temperature change across Africa with the value compared against the mean from 1986-2005. It highlights that they is three main bands of warming across the African continent. North Africa is projected to experience the spatially largest area and more intense warming, with annual mean temperature changes of up to 6 degrees by late 21st century. This intense projected temperature change is mirrored in Southern Africa; again with projections of up to 6 degrees of warming by late 21st century estimations. However, what is interesting is that central and Eastern Africa in projected to see annual temperature increases by late 21st century below that of the north or south from the RCP8.5 projections.

Temperature increases such as the ones projected will greatly impact water security across Africa. Increased temperatures increases evapotranspiration rates; so any surface water is more susceptible to evaporation (i.e. lakes and reservoirs such as Wemmer Pan in South Africa). This means that any surface water is going to disappear quicker than it previously would have done ceteris paribus. Whilst there is public policy and technological implementations, such as plastic black balls covering reservoirs to reduce evaporation, it is both costly and hard to implement in remote regions. Therefore, from these projections of dramatically increasing temperatures, surface waters are going to come under significantly greater pressure. Couple this with decreases in precipitation due to airs greater ability to hold water at higher temperatures, leading to reductions in mean precipitation, ground water stores can are also projected to be adversely affected by the increasing temperature projections; but we'll look at this negative externality in the next section just below in more detail.

So now we've looked at some of the effects of projected warming across Africa on water availability, we should now turn our attention to the projections of mean annual precipitation in Africa. I have used figure 1.2 already in previous posts, but it is a highly effective visual presentation of the projected changes to precipitation across Africa. It highlights three key projected outcomes.

1. Decreases in mean annual precipitation 'very likely' by mid-to-late 21st century in Northern and Southern Africa; with a larger spatial area affected in Southern Africa, with decreases of up to 15% stretching from South Africa up to the south of Zambia in the RCP8.5 projection

2. Increases of mean annual precipitation 'likely' by mid 21st century in Central and Eastern Africa, with subsaharan Africa potentially seeing a "greening" due to increased precipitation over the equator, with the ITCZ increasing its affected area increasingly northwards

3. Eastern Africa may experience more extreme drought event due to Indian Ocean warm pool warming; however, only projected as short term extreme events, with overall mean annual precipitation increases in the area

These projections would mean water availability and security in areas that are already dry is only going to become more insecure due to projected decreases in precipitation. However, I've only been able to scratch the surface of projections for water in Africa, so make sure to read the full IPCC Forth Assessment report that I have linked above to find out even more! It should be noted however, there is a cascade if uncertainty associated with current modelling and projection approaches. So any projection and effect should be taken with a pinch of salt and is just a prediction; however, they are becoming increasingly complex and accurate with substantial data inputted.

Next weeks blog is going to look at what these overall projections mean for water resources on first a national scale case study, and then subsequently a local scale example.

So now we've looked at some of the effects of projected warming across Africa on water availability, we should now turn our attention to the projections of mean annual precipitation in Africa. I have used figure 1.2 already in previous posts, but it is a highly effective visual presentation of the projected changes to precipitation across Africa. It highlights three key projected outcomes.

1. Decreases in mean annual precipitation 'very likely' by mid-to-late 21st century in Northern and Southern Africa; with a larger spatial area affected in Southern Africa, with decreases of up to 15% stretching from South Africa up to the south of Zambia in the RCP8.5 projection

2. Increases of mean annual precipitation 'likely' by mid 21st century in Central and Eastern Africa, with subsaharan Africa potentially seeing a "greening" due to increased precipitation over the equator, with the ITCZ increasing its affected area increasingly northwards

3. Eastern Africa may experience more extreme drought event due to Indian Ocean warm pool warming; however, only projected as short term extreme events, with overall mean annual precipitation increases in the area

|

| Figure 1.2 - Historical and projected annual precipitation change across Africa - IPCC (2014) |

Next weeks blog is going to look at what these overall projections mean for water resources on first a national scale case study, and then subsequently a local scale example.

This is a very good summary of the consensus on climate change in Africa but do note that it is from the 5th Assessment Report (AR5), not 4AR, of the IPCC! Might you consider in another post the relationship between projections and current trends? In East Africa, they are very different - it is known as the "East African Paradox".

ReplyDelete